The hardest part about moving to Vietnam was the dogs. Getting them cleared for international travel was a nightmare; vaccines, crates, paperwork, endless vet visits. But everything cleared without a single hitch. They made the long flight with me on 2-25-2010, and when we finally touched down in Ho Chi Minh City, Hong was waiting at the airport with her sister Tuoi and cousin Kiwi. The four of us stood there in the humid arrivals hall, my two dogs barking from their carriers, and for a second everything felt right.

Then our eyes met.

Hong looked sad. Not the fleeting kind of sadness you brush off, but something heavier, deeper in her expression. I’d seen that same look once before, back in October 2009, when she met me in Macau for those ten days before my first real visit to Vietnam. At the time I chalked it up to the stress of travel, or maybe the uncertainty of what came next. But it was the same shadow in her eyes now.

I understand it now.

She did love me, in her own fractured way. Not the clean, selfless love I imagined, but something tangled with guilt and fear. She knew what was coming. Her “owners”, the Triads, and even her family who controlled her life, her debts, her every move had already marked me as a target. They’d let the romance play out because it served them: a man willing to uproot his entire existence, bring money, bring assets, bring blind trust. But once I was settled, once the hook was set, they would decide when it was time for me to disappear. Murder at first, later shifted to a various criminal frame-ups when the pregnancy complicated things.

Hong knew the script. She had ran it herself and seen it run on others many times. I later found out that she married two western guys before me and that both were serving long prison sentences in Vietnam. She knew my fate would be grim the moment they gave the order. That sadness wasn’t just nostalgia or nerves. It was the quiet grief of someone who cared enough to feel the weight of what she was helping set in motion, but not enough, or not free enough, to stop it.

She greeted me with a hug, smiled for the cameras in my mind, helped load the dogs into the taxi; but the sadness lingered in her eyes the whole drive home. I mistook it for overwhelm, for the enormity of what we were starting. She knew it was the beginning of the end.

Starting in March 2010, I decided to try learning Vietnamese. I signed up for lessons, showed up consistently, practiced the tones and phrases. But progress crawled. The language felt like a wall I couldn’t climb, and after a couple months, I quit. It was frustrating, and I let it go.

Most days after that, I stayed close to home with Hong. Whenever I wasn’t in my home office on the computer, we watched television for hours, the kind of mindless local shows or dubbed movies that filled the time. Or we’d walk to a nearby spot for a foot massage. An hour cost three dollars. Cheap, relaxing, easy. It became routine.

Hong attempts suicide

Late March 2010. Hong tells me she needs to visit her mother, just after I’ve settled in for a month. She insists I stay behind. “Power’s always out down there,” she says. “Better if you wait here.” The way she says it, something’s off. The passports in our dresser, her sister’s, her cousin’s, are there, but not hers. That detail sticks.

I wait until she’s gone. I search her computer. There it is: an email sent just a week before I moved to Vietnam. The IP address isn’t local. It’s Singapore. She never mentioned Singapore. Not once. What else hasn’t she mentioned?

I call her while she’s still at her mother’s place. “Where’s your passport?” I ask. I want to see proof. She dodges, says she’ll show me when she gets back. The evasion makes me angry. Why lie about a trip to Singapore? What’s she hiding?

Before she returns, I dig deeper. Run a low-level analysis on her hard drive; deleted cookies, digital footprints. She has a Facebook account I’ve never heard about. I find her username, crack the password using patterns I know. Inside, I find messages with a guy in Singapore. He’s pouring his heart out to her.

I slip into her online skin, talk to him as if I’m her. He’s naive, maybe a virgin. From what I gather, it was just a kiss. Still, she lied. If she lied about that, what else? I tell her it’s over.

She comes back in tears, finally produces the passport. The stamps don’t lie; three weeks in Singapore, right before I moved. She said her family needed money and she didn’t want to ask me for it, so she went there to work. I lash out, tell her I should’ve chosen the other girl, Phuong. “You’re no good,” I say. I leave for a foot massage to clear my head.

When I return, she’s in bed. She tells me she’s taken 24 sleeping pills. I rush her to a clinic. The staff only speak Vietnamese. Hong translates: they say she’ll be fine if she gets to a hospital within 24 hours. The logic doesn’t add up. I haven’t slept in two days, but I’m not taking chances. I force her onto the motorcycle. It’s 2 a.m. I drive like hell, yelling the whole way.

The only thing keeping Hong conscious was the way I tore through the city; reckless, relentless. That panic kept her awake, kept her alive. When we finally burst through the hospital doors, the place was chaos. It looked like a field hospital in a war zone. Bodies everywhere, sprawled on the tile; no beds, no stretchers left. Most of them were motorcycle wrecks, late-night drunks colliding on the streets. One man clutched his own intestines, red slicked across the floor. Another’s eye dangled loose from his face. The air was thick with pain; anguish, moaning, the sound of lives unspooling.

I flagged down a nurse who thankfully understood enough English. Showed him the empty pillbox. His eyes widened, alarm flashing across his face. He disappeared, came back with a doctor. The doctor’s hands trembled as he checked Hong’s pulse. Blood everywhere, bodies waiting, but he didn’t hesitate; he put her on a gurney and wheeled her outside, right onto the sidewalk. No space inside. They started pumping her stomach within five minutes.

The doctor looked at me, grave. “She would have been dead in twenty minutes if you’d waited.”

I didn’t know it then, but Hong was one week pregnant with our son. That night, I saved two lives. Only later did I learn the truth: Hong’s friend told me she took the pills out of fear. She thought the Triads would sell her as a life-long slave for botching the scam by running off to Singapore without covering her tracks. That was the real threat hanging over both our heads.

This photo, snapped in the hospital hallway, captures Hong just after they pumped her stomach. The space looks sterile, but to the right, the wall opens directly onto a courtyard, exposed to the night air. That’s where they left her, unmoving on a gurney, for three hours. No privacy, no comfort, just a thin line between inside and out. Eventually, a room opened up. They admitted her overnight. By the next day, I brought her home, both of us changed by what happened in that corridor.

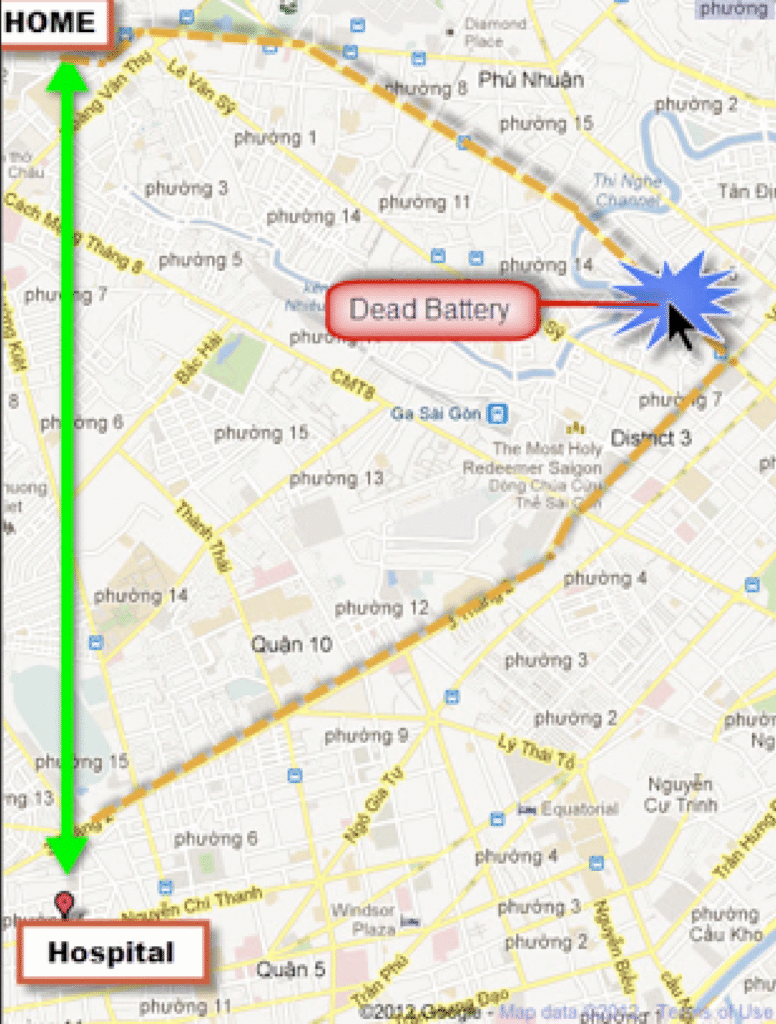

The map shows the route I took that night; point A, our house, to point B, the hospital. I’d never made that drive before. The arrow at the top marks where we lived; the one at the bottom, the hospital where they saved her life. I didn’t know the way. If Hong had lost consciousness, we’d have been lost; no directions, no backup, nothing. My phone battery died somewhere along the ride. The truth is, if she had blacked out, both she and our unborn son wouldn’t have made it. We survived that night on adrenaline, luck, and nothing else.

We reconciled in that hospital room, both of us exhausted and raw. I tried to let it go, tried to move forward like nothing permanent had cracked between us. But the truth lingered, just out of reach. No matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t shake the sense that she was hiding something else. That feeling never left me. Time would prove me right, though I couldn’t have imagined just how deep the secrets ran. The answers didn’t come all at once, they arrived in fragments, each one heavier than the last.

Then, just a couple weeks after the overdose, Hong told me she was pregnant. She had found out she was pregnant before they released her from the hospital but waited to tell me. Suddenly, the stakes shifted. She insisted that having a child outside of marriage would disgrace her family. The pressure was immediate; she needed a wedding, and fast. Two months in Vietnam, and I was being nudged toward a shotgun ceremony.

I knew the marriage wouldn’t hold up in the eyes of the U.S. government. On paper, it meant nothing back home. But for her, it was everything. I said yes. If keeping her family’s honor intact was the price, I was willing to pay it. For a while, I convinced myself that was reason enough.

THE WEDDING: Nearly 450 people drifted in and out that day, most of them strangers to me. My only ally was Johnny; a wild card I’d flown in three days earlier. I’d spent weeks practicing a Vietnamese toast, determined to get it right. When the moment came, Hong vanished, slipping away before I could speak. At the time, I chalked it up to nerves. Now I know better; she couldn’t bear to stand there while the crowd, all in on the secret, watched me play the fool. Only Johnny and I believed the wedding was real. For Hong’s family, this was routine. I was just the latest mark, one step from disaster, and the wedding gave their scam the legitimacy it needed to escalate.

The setting was surreal; deep in the jungle, at her parents’ house. Hong had hired seven ladyboys to perform, and they didn’t hold back. Tops came off, oblivious to the kids weaving through the crowd. It was chaos, spectacle, and farce, all rolled into one. A night you couldn’t forget, no matter how hard you tried.

They pull out all the stops for these weddings; not for love, but for the con. Everything is staged: the crowd, the videographer, the orchestrated chaos. It’s all designed to erase any doubt about the marriage’s legitimacy. If you disappear, arrested or worse, there’s a professional wedding video to wave in front of authorities, proof you belonged, proof you were part of the family. That’s how they keep your money after you’re gone. The scam is clinical, practiced. They’ve refined it to an art.

Hong once let it slip: there are a few Americans locked up in the remote jail near her father’s house. No expats live within a hundred miles of that place. In Vietnam, prisoners don’t get shipped off to distant cities, they stay put, close to whoever put them there. According to Hong, those Americans were set up by women just like her. The scam doesn’t end with the arrest. Families back in the States send money for better food and living conditions, another revenue stream for Hong’s family. It’s unlikely those men ever realize who really betrayed them; the setup is meticulous, the blame always redirected, the truth buried under layers of misdirection.

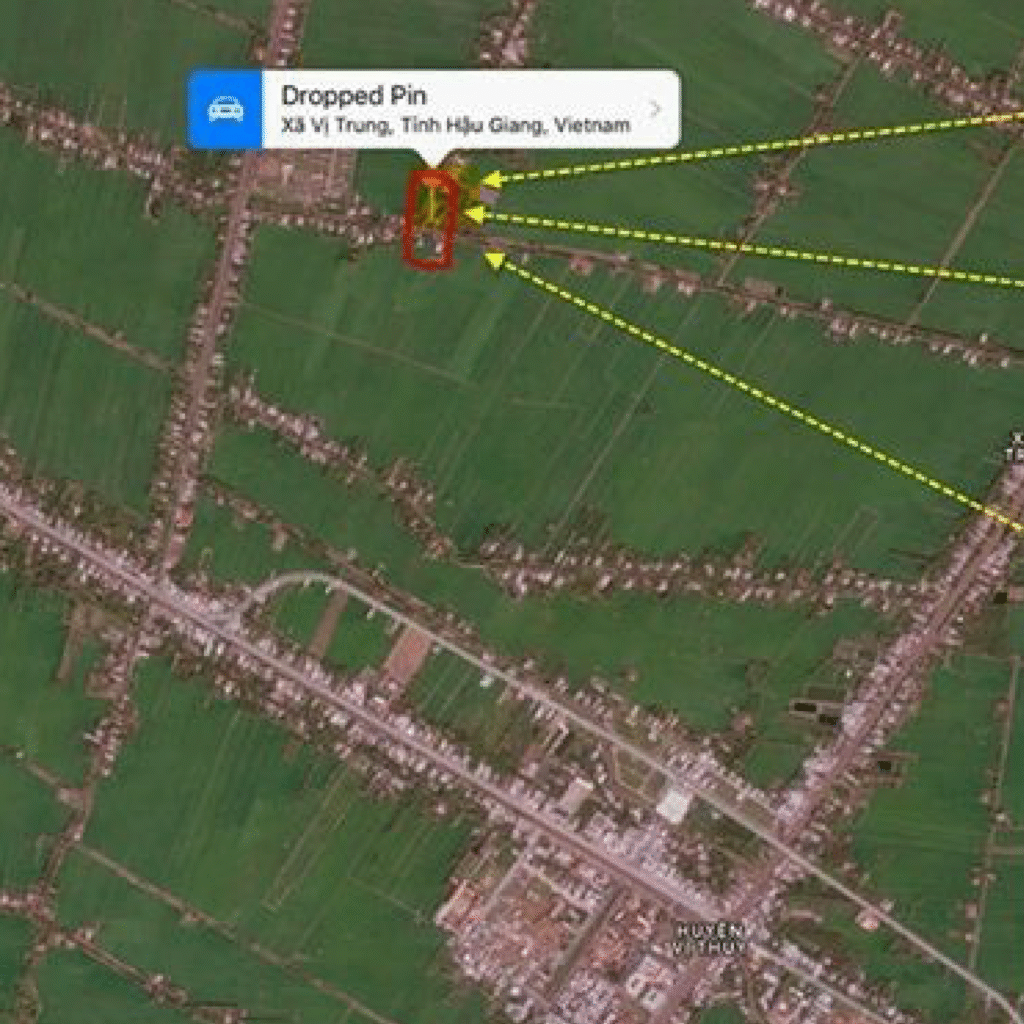

On the map below, you can see the layout: “1” marks her father and uncle’s homes, the site of our wedding. “2” is the prison—where Hong claimed the Americans are held, where the warden is a close friend of her father. I learned later the warden once scolded Hong for not framing me sooner. The other yellow blocks? More family—her aunts and uncles, all woven into the same tight web.

The Wedding Video

Wedding Location

The Wedding Party

July 2010 – The Macau Trips Begin

After the wedding, the cracks widened. Hong and I fought constantly; every argument rooted in another lie I’d uncovered about her past. The tension never let up. Vietnam had a way of turning days into slow, colorless stretches. Restlessness was my baseline. Then her friend “7” appeared, inviting me to spend five days at her place in Macau. That trip marked the start of a routine: every five weeks, I’d escape Vietnam for a stint in Macau.

This was August 2010. Hong always said the same thing before I left: “Have fun, just don’t fall in love with anyone.” I was isolated in Vietnam, desperate for any distraction. The Macau trips became my lifeline. Hong’s friends treated me like royalty; six to eight women orbiting me at all times, unless “7’s” husband showed up. He never joined us when we went out. I thought he just wasn’t interested in the nightlife.

I was wrong. While the girls pulled me out to discos, “7’s” husband stayed behind, hacking into my computer. Every outing was orchestrated. The attention, the fun, the sense of belonging; it was all bait. I didn’t see it then, but I’d walked straight into their trap, trusting them like family while they set the stage for my downfall.

In the photo below, Kieu stands on the left, “7”—real name Ngoc My Linh—on the right. “7” once told me she got her nickname because she ran away at eleven and didn’t come back for seven years, returning at eighteen. Hong disputed that, said the truth was less dramatic: “7” left at fourteen, sent off to earn money for the family.

Their mother always seemed gentle, almost out of place in that house. Their father though; he radiated menace. I remember visiting once and seeing “7” break down, sobbing and screaming out of nowhere. Her father just sat there, cold, repeating “Du Me”, a curse that cuts deep in Vietnamese. The reason for her outburst came out later: she’d discovered her father had stolen $5,000US, money she’d given her mother to hold, meant for buying property. Her father forced her mother to hand it over and then squandered it on his mistress and gambling.

The family’s darkness ran deeper. “7’s” father had raped her older sister, Nhan, when they were kids. That house was built on secrets and survival—every story, every nickname, another layer in a history you could feel but never quite see.

“7” was the undisputed boss of the girls; the center of gravity for all of them. Her triad husband “AKA John Lam” split his time between Hawaii and Macau. He and I bonded over a shared obsession with computers. John had a knack for making you feel important. He’d ride with me in the taxi back to the airport when it was time for me to return to Vietnam, always insisting on paying the fare, even walking me inside to make sure I got checked in without a hitch.

Looking back, I see the strategy. It wasn’t just hospitality; it was surveillance. They wanted to know where I was, who I spoke to, keep the operation airtight. But in the moment, I let myself believe it was genuine friendship. The Triad connection faded into the background. I understood they liked me for my money, for what I could offer, but that didn’t bother me. It wasn’t the whole story, or so I told myself.

They were masters at filling the void; making you feel loved, seen, included. When you’re 8,000 miles from home, unable to communicate with almost everyone around you, that kind of attention is a lifeline. It’s also the perfect setup. Loneliness makes you vulnerable, and they know exactly how to turn that vulnerability into opportunity. The photo below shows John and “7” at their wedding—a snapshot of a world where nothing was as it seemed.

There’s a moment from John and 7’s wedding that still sticks with me. A singer worked the crowd, weaving through tables, and stopped right in front of me, belting out a song inches from my face. I didn’t think much of it at the time. Sitting beside me was my interpreter, a guy who’d grown up in America since he was fourteen. He was street-smart, but naïve about the subtle codes and old wounds still alive in Vietnam. His family’s story was complicated; his grandfather, an American soldier, had fathered a child with his Vietnamese grandmother during the war. When the Americans pulled out, his grandmother destroyed every trace of the man’s existence, terrified the Communists would find out and punish the family. His father, half-Vietnamese but looking nothing like it, grew up speaking only Vietnamese and suffering for his American blood.

They were good people, his family; no grudge against Americans, just survivors of a brutal history. That night, as the singer serenaded our table, my interpreter leaned in, translating bits and pieces. Only later did he realize the truth: the man was singing a Viet Cong war song, a victory anthem about killing the enemy. The crowd found it hilarious. I was being mocked, the butt of the joke, and didn’t even know it. Nearly 400 people watched as the song’s message—“we will kill you and be victorious” was delivered straight to my face. The laughter was for them, not for me.

The Drug Trap

Drugs were never really my thing. I didn’t even touch alcohol until I was twenty-eight, thanks to a teenage run-in with peppermint schnapps that left me violently ill and off booze for over a decade. When I finally started drinking again, it was red wine—nothing wild.

But in Hong’s world, things were different. Her friends always had something to smoke—what they called “designer ephedra.” In reality, it was “ice.” They’d crowd around me, grinning, holding it out, coaxing me to join in. Hong would laugh it off: “That’s just how they show you they like you. They want you to feel special.” Maybe so. But when you’re a foreigner, isolated by language and culture, desperate to belong, it’s hard to keep saying no. Eventually, I gave in.

The high created an instant bond. Suddenly, I was part of the group. They’d give me endless massages, and one by one, her friends would make moves on me. Hong’s only rule: have fun, just don’t fall in love. So I did. I let myself think I was living the dream; buying gifts for everyone, fixing their iPods, hitting discos with a pack of women and no competition. I felt like a rock star.

But looking back, I see it for what it was. They were gathering intel, mapping out my weaknesses, pulling me deeper into their web. I was too busy enjoying the attention to notice I was being set up from the start.

Typical Day at 7’s in Macau

I shot this video at DD3 Disco in Macau, surrounded by Hong’s friends, the music thumping, neon everywhere. The next day, my brand-new MacBook’s hard drive was dead; completely fried. I didn’t put it together back then, but now it’s obvious: 7’s husband, John, was behind it. While we were out at the club, he was back at the house, hacking into my laptop. That was the real reason they insisted I stay at 7’s place—so they’d have access to my computer whenever they dragged me out for a night on the town, or to test how far I’d go, what lines I’d cross, and which cons might work best on me.

John always played it cool. Before we’d leave for the disco, he’d pretend to be asleep on the couch. I never thought twice about it. In hindsight, every move was calculated. I was too busy living in the moment to see the setup unfolding around me.

I only went out to the disco with Hong’s friends four times in Macau, but nearly every time, things got tense; three out of four nights, I was inches from a fight. Looking back, I realize those confrontations weren’t random. They were staged, each one a test. They wanted to see how I’d react under pressure, to gauge my nerve and decide which scams might work on me.

Every time, I stood my ground. I didn’t flinch, didn’t show an ounce of fear. The first time, it was a single guy; the next, two; then three. If I’d backed down, they had a plan ready: lure me into sleeping with the boss’s wife; 7’s husband’s boss. She did come on to me, but I wasn’t interested. When they saw I wouldn’t take the bait, and that I wouldn’t scare easy, they dropped that angle. The goal was clear: get me to cross a line, then blackmail me, threaten me with violence unless I paid up. But I didn’t bite.

The two main spots they took me—the ones they used for all their marks—were called DD2 and DD3. DD2 felt safer; DD3 was crawling with Triads, ninety-nine percent of the crowd. Most of the trouble happened there.

In the photo, you see Yuri, one of 7’s friends, and her Triad husband, a man I never met in person. In the background, his entourage is always close, eyes on every angle. He’s got four wives and can’t even use the bathroom without a squad of goons shadowing him. No surprise, considering how many people they’ve burned. Paranoia is just part of the job description.

Criminals in Asia

Hollywood gets it wrong. The criminal underworld in Asia isn’t all glowering tattooed heavies and tough-guy posturing. The real operators approach you with a smile. They’re sharply dressed, polished, running legitimate businesses as a front. The evil happens out of sight; calculated, precise, and far darker than anything you see on screen.

Their goal isn’t just to take your money. They want everything; your trust, your dignity, your sense of self. They’ll strip you bare and leave you doubting your own instincts. The cruelty is casual, woven into the fabric of daily life. It’s no mystery why women suffer so much abuse in these circles; when men like this operate unchecked, empathy gets buried. And the so-called “good” men? They keep their heads down. The culture is tight-lipped; no one speaks up, even if they disagree. Silence is safety.

I’m not painting all Asian men with the same brush; far from it. I know the difference. But the criminals I encountered were everywhere, and their mastery of deception makes it nearly impossible to know who you’re really dealing with. You learn to expect the unexpected. The only thing that rattles them is someone who won’t flinch, who refuses to show fear. They need you to cower before they strike; if you stand your ground, they hesitate.

For nearly two months in 2011, I had a rotating crew of five or six men camped outside my house, parked at a coffee shop, eyes on me eight hours a day. They used smartphones to control my computers; my ex had helped them infect everything. Every time I left, I stared them down. They’d look away, every single time. Underneath the bravado, they were cowards. But make no mistake; if given the chance, they’d cut your throat without a second thought and sleep just fine afterward. You have to be ready for anything. It’s not like America, where you can spot hostility a mile away. Over there, the deception is an art form. I was dealing with the worst of the worst, but I’ll say this: I have enormous respect for Asian cultures and people. Statistically, Asians commit the least crime of any group in America. But don’t let that lull you into complacency; Asia has its share of predators, and they’re very, very good at what they do.

I’d been warned; more than once. Americans who’d spent years in Asia, or made regular trips, pulled me aside and told me straight: “You’re being set up.” They explained how it worked. The girls working at the saunas were professionals, trained to make Western men fall hard and fast. The goal was simple: get you to move across the world for them. But moving wasn’t a requirement. Most of their marks were just visitors; guys who’d come for a week, get their computers hacked by the Triads, and then find themselves blackmailed months later. The scam was always tailored to the victim.

For those who did relocate, the playbook was more elaborate. They’d try to get you hooked on drugs, drive a wedge between you and your family, monitor your every move, and slowly isolate you from your assets. When the time was right, you’d simply vanish. Back home, your family would write you off as another casualty; lost to addiction, depression, or some imagined midlife crisis. You’d stop calling, fade from memory, and disappear into the static.

That nearly became my story. I was right on the edge. But then my son was born, and something shifted. Maybe it was luck, maybe something else, but I got a second chance. That, more than anything, changed my fate.

Love in Return

In the end, every one of the girls joined in on the scam. But looking back, I can see that some of them started to care about me for real. It wasn’t just wishful thinking—I remember the way they’d undermine each other, how some tried to warn me, even as the con played out. There were small acts, quiet moments where their loyalty to the group wavered and something genuine slipped through. I wanted to save them all. Maybe they sensed that, maybe it was just the first time someone had cared about them in a way their own families never did. It wore on them.

Hong’s friend “7” tried to warn me more than once. She told me outright: Hong wasn’t a good person. She even confessed that when I first met Hong and handed her $4,600, it was “7” who got the call from the hotel bathroom while Hong cried. “Give the money back,” “7” told her. “It’ll make him love you, make him want you.” She was right. That single act set everything in motion.

Hong wasn’t just a conspirator; sometimes, she was my only warning. She’d betray her own circle and family to protect me, but I was too naïve to see the danger for what it was. I shrugged off her cautions, convinced these people were my friends.

She warned me about 7’s husband, John—told me he was jealous, that I should think about why a man like him would tolerate another guy coming in and stealing the spotlight. She told me not to go anywhere alone with him, especially that October in Macau, after a blow-up where Nhung confessed to “7” that she loved me and didn’t want to work in Macau anymore. At the time, I didn’t understand: Nhung was refusing to go along with the scam, and that made John furious. If she left, he’d lose his cut from the sauna. Hong told me John thought I was playing games, and she and Nhung believed he was planning to lure me out and have me killed. I still didn’t fully believe it, but I trusted my gut enough to refuse when John asked me to go with him.

Later that same night, John ordered food, kept insisting I eat. I said no. He ignored me, just kept pushing. The whole thing felt off; surreal. I’m convinced now he tried to drug me. Hong thought he might have planned to kill both me and Nhung, afraid she’d tell me the truth. Back then, I still doubted her, but John’s reaction when I told him Hong suspected he wanted me dead was pure shock; like he couldn’t believe one of the girls would turn against the Triads.

That was October 2010. The next day, before I left for Vietnam, “7” hurled something at John after her older sister Nhan broke down in front of us, calling him a snake who smiles while stabbing you in the back. Later, I learned it wasn’t just about the previous day’s plan; John still intended to have me killed. It became clear that “7” and Nhan cared for me like family. I was never intimate with either of them, but I was with 7’s younger sister Kieu and their friend Nhung.

Four months later, in February 2011, “7” told me Kieu loved me, and again warned me about Hong. She said Kieu kept trying to say Hong wasn’t a good person. I was generous with all of them; gifts, kindness, no strings attached. Most men who came to Macau were much older, just looking for sex. I was different; under forty, in shape, and I genuinely cared. That changed things. It tested their loyalty to the Triads, to their families. Over time, my care for them tore at their hearts. I remember Kieu calling me in tears, saying, “You’re so good,” but she wouldn’t say why. Now I know; she loved me but was trapped, forced to play her part.

I cared deeply for all of them. That’s why, when John finally told me the truth; that they’d all been scamming me from the start. The fall was devastating. The betrayal wasn’t just financial. It was personal. It cut all the way through.

Below are pictures of Nhung, 7’s older sister Nhan and 7’s cousin “Baby.” I know that Baby cared about me because she cried in front of me one time out of nowhere, and towards the end, she was never happy like she always was when I first started hanging out with them in Macau. I also remember when Kieu called me crying, saying that she has problems with Baby about something she wrote in her diary. I now know it was pertaining to her being sad about what everybody was doing to me, and Kieu felt terrible because she was starting to care about me. She felt horrible for being involved in the evil plot to bring me down. Still, she was being pressured by her Father, John Lam, and the other behind-the-scenes Triads who do this all of the time but probably never fail due to their absolute patience and attention to detail.

Nhung

Nhan & Baby

7 & Her Crew

At the very start, there was Phuong, someone I met at the same time as Hong. When I chose Hong, I let Phuong drift out of my life. We didn’t speak again until April 2011, when I ran into her in Macau, more than a year after I’d moved to Vietnam.

Phuong called me the day after I arrived, her voice urgent. She tried to warn me, but I didn’t grasp the meaning. She told me, “Don’t take iPhones that belong to other people.” At the time, it sounded cryptic, almost random. Only later did the pieces click into place. She was talking about the iPhone “7” and John had pressed into my hands on April 14th, 2011, the so-called “Airplane Scam.” That phone was a clone of mine, loaded with planted evidence: fake text messages to a number in China, designed to make it look like I was involved in something criminal.

Phuong was trying to protect me. Even after all the distance, all the betrayal, she cared enough to try to steer me clear of the trap. I just didn’t understand the warning until it was almost too late. Below is a picture of Phuong “Hanna”, taken in July 2009 by me while with her in Macau.

December 2nd, 2010 – My Son is Born

When Hong got pregnant, it was right around the time I landed in Vietnam, on February 25th, 2010. She didn’t know for sure if I was the father, or if it was her Vietnamese ex, Cuong Nguyen. When the time came for the birth, she kept me out of the delivery room. The moment our son was born, at 11:43 PM on December 2, 2010, her cousin whisked me away to buy baby formula, keeping me from seeing him. I didn’t realize it at the time, but Hong needed to be certain. If the baby had looked unmistakably Asian after they cleaned him up, the plan was to have me killed before I ever made it back to the hospital.

Her cousin drove me in circles for half an hour, pretending not to know where to buy formula. Then, a call came in from Hong. Suddenly, she knew exactly where to go. The formula was never even opened, Hong breastfed from day one. I didn’t piece it together until much later, after I’d moved back to the U.S. with my son. A friend of Hong’s told me the truth: people were waiting for the go-ahead to kill me. The cousin was supposed to lead me right to them. But after Hong called and confirmed the baby was mine, the hit was called off.

Hong let another detail slip later. Cuong Nguyen left for America two days after my son was born. He’d been hoping the baby was his, and when he realized he wasn’t, he left Vietnam in anger. He returned five months later, on April 15th, 2011, just a day after the Airplane Scam. We were both in the air, crossing paths. Cuong planned to pick up where I left off, assuming I’d be locked up for good. Hong and Cuong started reconnecting in secret a few months prior, plotting as my situation came to fruition.

If my son hadn’t been mine, I wouldn’t have survived. Each of us, in different ways, saved the other’s life. Since coming back to the States, I’ve spoken with two Korean businessmen who know these scams inside out. Both were stunned I’d managed to escape. According to them, once you’re marked, there’s no getting out. The Triads use women as bait, targeting anyone with money; race doesn’t matter. Scamming foreigners is big business, and I was just another mark who nearly didn’t make it out alive.

New Year’s Eve December 31st, 2010

This photo was snapped on December 31st, 2010, at 11:45 PM. It looks unremarkable; a typical New Year’s Eve moment. But just an hour later, Hong and her circle would set their plan in motion. At the time, I had no idea what was about to unfold. The smiles in the picture hide the truth: behind the celebrations, betrayal was already taking shape.

An hour after that photo was taken, everything shifted. We left the nightclub, piled into a taxi. Hong claimed her brother got sucker-punched as he was getting into the backseat. I was in the front, didn’t see or hear a thing. She didn’t tell me what happened until we were nearly home; no warning, no chance for me to intervene. She knew I would’ve jumped in; that wasn’t what she wanted.

When I first arrived in Vietnam, Hong seemed sincere. She’d talk about cutting ties with old friends, insisting they were only after her money. She even warned me about Giang, called him evil, said she kept him away to protect me from scams. So when her loyalty began to shift, she needed a reason to bring Giang into our lives. Calling him to “defend” her brother was the perfect cover.

Giang showed up with three friends within five minutes, at 1 AM on New Year’s Eve. He was a known drug addict, and there’s no way four guys drop everything, including their habits, to answer a call that quickly, especially for someone they hadn’t seen in a year. Giang didn’t even live that close. The whole thing was staged.

Just two weeks before, I’d brought $1.5 million in Chinese Yuan into Vietnam, on top of the $100,000 in Yuan and $50,000 in U.S. cash I already had. The temptation was too much. They decided it was time to act.

We went back to the nightclub, but the so-called attackers had vanished. Later, Giang would back out of killing me twice. Maybe that first night, he and his friends were supposed to do it but got cold feet when they saw my size; 6’3”, 225 pounds, a giant by local standards. Or maybe it was just a setup, a way to meet me, make me feel indebted, and pave the way for future betrayals.

That photo from earlier means more than it seems. Hong looks completely at ease; loving, normal, no hint of what was coming. That’s the danger: the poker face, the ability to mask betrayal with a smile. I’ve studied her eyes in countless pictures and never found a trace of deception. These people are masters. They wrote the book on hiding intent. And that’s what makes them so dangerous.